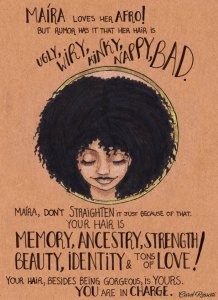

It was the Monday night after the Oscars and I can remember browsing through my Twitter feed to see what interesting information about the world I could learn about on this particular night. I can vividly remember coming across a tweet of a video of Giuliana Rancic, a reporter from the television channel E! on the infamous style show Fashion Police. Now I love everything about fashion and try to keep as up to date as possible on the latest styles and trends. I used to be a loyal fan of the show Fashion Police as well, but the comments that Giuliana Rancic made about Zendaya Coleman, an 18-year-old actress who is known for her strong fashion sense, boiled my blood to say the least. In the tweeted out video, Rancic is seen making a comment about Zendaya’s outfit of choice and hair for the Oscars. Rancic makes the joke that Zendaya’s hair (which were faux locs) probably “smells like patchouli oil or weed.” Dreadlocks is a hairstyle that can be worn as an expression of deep religious or spiritual conviction, ethnic pride or fashion preference.  The first example of dreadlocks has been dated back to North Africa and the North Africa. In America, this is one of the many hairstyles of the African American community and is normally not an acceptable style in a professional setting. So when I heard the comments uttered by Giuliana Rancic, I would be lying if I said I was shocked and surprised. However, I was still deeply offended, as was Zendaya. Oftentimes, Black people are told that our hair isn’t good enough and that in order for it to be good enough, we have to chemically modify it. It is rare that you see a Black celebrity wearing her natural hair. She often has some type of extensions in and her hair is always straight even though Black people’s hair is naturally curly. Rancic’s comments were also completely ignorant. She made reference to weed and patchouli oil when critiquing Zendaya’s hair. These two references are common stereotypes of Black people. The patchouli oil reference refers to the common notion that all Black people carry some type of odor. The weed reference refers to the stereotype that young Black people often smoke weed, particularly those with dreadlocks. I think the lesson from this incident that is to be learned is not only the importance of intent vs. impact but also on how uneducated public figures are about different cultures. Rancic had no idea how offensive and ignorant her statement was and even tried to defend it initially after it blew up on social media. I think this example shows just a small part of the struggle Black women have to go through in a public space. There are so many things about a Black woman that are not seen as good enough. This is just one example of that. I think the best part of this whole incident is Zendaya’s response. She perfectly sums up the feelings of most Black women and the ridicule we face just for displaying our hair in all of its natural glory. And of course, this still isn’t good enough. Here is her statement:

The first example of dreadlocks has been dated back to North Africa and the North Africa. In America, this is one of the many hairstyles of the African American community and is normally not an acceptable style in a professional setting. So when I heard the comments uttered by Giuliana Rancic, I would be lying if I said I was shocked and surprised. However, I was still deeply offended, as was Zendaya. Oftentimes, Black people are told that our hair isn’t good enough and that in order for it to be good enough, we have to chemically modify it. It is rare that you see a Black celebrity wearing her natural hair. She often has some type of extensions in and her hair is always straight even though Black people’s hair is naturally curly. Rancic’s comments were also completely ignorant. She made reference to weed and patchouli oil when critiquing Zendaya’s hair. These two references are common stereotypes of Black people. The patchouli oil reference refers to the common notion that all Black people carry some type of odor. The weed reference refers to the stereotype that young Black people often smoke weed, particularly those with dreadlocks. I think the lesson from this incident that is to be learned is not only the importance of intent vs. impact but also on how uneducated public figures are about different cultures. Rancic had no idea how offensive and ignorant her statement was and even tried to defend it initially after it blew up on social media. I think this example shows just a small part of the struggle Black women have to go through in a public space. There are so many things about a Black woman that are not seen as good enough. This is just one example of that. I think the best part of this whole incident is Zendaya’s response. She perfectly sums up the feelings of most Black women and the ridicule we face just for displaying our hair in all of its natural glory. And of course, this still isn’t good enough. Here is her statement:

There is a fine line between what is funny and disrespectful. Someone said something about my hair at the Oscars that left me in awe. Not because I was relishing in rave outfit reviews, but because I was hit with ignorant slurs and pure disrespect. To say that an 18 year old young woman with locs must smell of patchouli oil or “weed” is not only a large stereotype but outrageously offensive. I don’t usually feel the need to respond to negative things but certain remarks cannot go unchecked. I’ll have you know my father, brother, best childhood friend and little cousins all have have locs. Do you want to know what Ava DuVernay (direct of the Oscar nominated film Selma), Ledisi (9t time Grammy nominated singer/songwriter and actress), Terry McMillan (author), Vincent Brown (Professor of African American studies at Harvard University), Heather Andrea Williams (Historian who also possesses a JD from Harvard University, and an MA and PhD from Yale University) as well as many other men, women and children of all races have in common? Locs. None of which smell of marijuana. There is already harsh criticism of African American hair in society without the help of ignorant people who choose to judge others based on the curl of their hair. My wearing my hair in locs on an Oscar red carpet was to showcase them in a positive light, to remind people of color that our hair is good enough. To me locs are a symbol of strength and beauty, almost like a lion’s mane. I suggest some people should listen to India Arie’s “I Am Not My Hair” and contemplate a little before opening your mouth so quickly to judge.” If I was faced with the same criticism as Zendaya about my hair, I honestly couldn’t have said it more eloquently. She perfectly responds respectfully and graciously to such offensive comments.

There is a fine line between what is funny and disrespectful. Someone said something about my hair at the Oscars that left me in awe. Not because I was relishing in rave outfit reviews, but because I was hit with ignorant slurs and pure disrespect. To say that an 18 year old young woman with locs must smell of patchouli oil or “weed” is not only a large stereotype but outrageously offensive. I don’t usually feel the need to respond to negative things but certain remarks cannot go unchecked. I’ll have you know my father, brother, best childhood friend and little cousins all have have locs. Do you want to know what Ava DuVernay (direct of the Oscar nominated film Selma), Ledisi (9t time Grammy nominated singer/songwriter and actress), Terry McMillan (author), Vincent Brown (Professor of African American studies at Harvard University), Heather Andrea Williams (Historian who also possesses a JD from Harvard University, and an MA and PhD from Yale University) as well as many other men, women and children of all races have in common? Locs. None of which smell of marijuana. There is already harsh criticism of African American hair in society without the help of ignorant people who choose to judge others based on the curl of their hair. My wearing my hair in locs on an Oscar red carpet was to showcase them in a positive light, to remind people of color that our hair is good enough. To me locs are a symbol of strength and beauty, almost like a lion’s mane. I suggest some people should listen to India Arie’s “I Am Not My Hair” and contemplate a little before opening your mouth so quickly to judge.” If I was faced with the same criticism as Zendaya about my hair, I honestly couldn’t have said it more eloquently. She perfectly responds respectfully and graciously to such offensive comments.

This post encouraged me to keep being proud of my hair and make no apologies of how different it is from society’s standard of beauty. It definitely reminded me that “I Am Not My Hair.” This incident serves as an example as to the importance of intent vs. impact. Black Hair is beautiful.  Mica Cunningham is a 3rd year Chemistry/Pre major and a Medical Sciences Minor and a 2nd year WILL participant.

Mica Cunningham is a 3rd year Chemistry/Pre major and a Medical Sciences Minor and a 2nd year WILL participant.